| Главная » Иные статьи » Фонология и письменность Кхуздӯла |

Текст был раньше доступен на сайте: http://lotrplaza.com/dwarves/Khuzdul_lect.asp В настоящее время ссылка не работает. Khuzdul is the language Tolkien devised for the dwarves… and Khuzdul is the language Mahal taught them before they were put to sleep under the mountains. It is important to know something about the attitude the dwarves have towards their language. Tolkien describes the dwarves as ‘secretive, acquisitive, laborous, retentive of the memory of injuries[…]It is according to the nature of the Dwarves that in travelling, and labouring, and trading about the world they should use ever openly the languages of the Men among whom they dwell; and yet in secret (a secret which unlike the Elves they are unwilling to unlock even to those whom they know are friends and desire learning not power) they use a strange slow-changing tongue. (HoME 12 p.22) Tolkien also wrote:

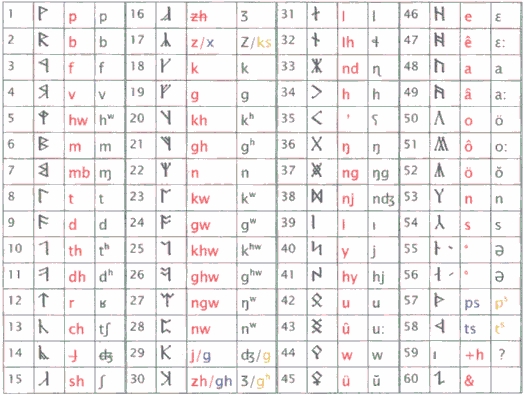

The father-tongue of the Dwarves Aule himself devised for them, and their languages have thus no kinship with those of the Quendi. The dwarves do not gladly teach their tongue to those of alien race; and in use they have made it harsh and intricate.’ (HoME p.295) Khuzdul is a secret language, a ritual language which dwarves use mostly for recording, ceremonies and namegiving. The dwarves’ khuzdul names are never divulged, and never written down. The secrecy goes so far that they have adopted a whole set of Mannish names to identify themselves outside of their own language. The corpus of attested words in Khuzdul is very small… maybe a set of at most fifty words…and the bulk of them consists of place names. There is exactly one exclamation which could be seen as a phrase… Gimli’s war cry ‘baruk Khazâd ai-mênu’. However, luckily Tolkien usually gave a translation of the names so that it is possible to guess at the meaning of the individual elements in the words. Although Tolkien had a set of grammatical rules in mind when creating his few expressions and words, it is hard to decide what they might have been. The scarcity of the corpus means that without an explicit statement on Tolkien’s side interpretations are wide open. It also means that when talking about Khuzdul we cannot actually talk about a ‘language’, only about some fragments of it, fragments which are barely enough to give us an idea what the actual language might be like.Khuzdul A This is where Khuzdul A comes in. It is important to underline that Khuzdul A is by no means Tolkien’s Khuzdul, but it is based, wherever possible, on what we can know, or extract, or conjecture from the existing corpus. It is also important to see that some of the conclusions done on the existing corpus might later be disproven by more linguistic evidence which is, at the moment, not available. However, there are a few things we do know about the way Tolkien went about to create Khuzdul words, one of them is that he used the idea of radical roots. This is an important concept which is the base of all word formation in Khuzdul A. But what does it mean? Radical roots are a set of consonants which determine the basic sense of the word. Its grammatical function of verb, adjective, noun is then determined by the addition of vowels, prefixes and suffixes. Once this principle is understood it is relatively simple to determine whether a word within a context is a verb, a noun, or an adjective as each word class displays a different set of vowels. This also means that words are less likely to undergo consonant changes like assimilation, because the consonants are important carriers of meaning. Changing the consonant means changing the meaning. This is one reason why Khuzdul is also a fairly unchanged language, aside from the dwarvish tendency to be conservative about changes. The radical root system of word formation is taken from the Semitic language systems; Arabic, and Hebrew. This is one reason why we opted to orient ourselves widely on the Arabic grammar while deciding about grammatical features. This makes the language quite distinct from the more indo-european system of the Sindarin and Quenya. We have also aimed at trying to retain that harsh sounding character which Tolkien describes as being typical for Khuzdul. It is also something which all of you should bear in mind when going about creating new words. However, actual rules for word formation will be the subject for the next lecture. In this lecture I just want to take a look at the phonemic system of Khuzdul What is a phoneme?… it is a sound element…. Basically a vowel or consonant. Every language has its own set of typical sounds which make the character of the language. There are rules about which phonemes can go side by side, rules which also change from one language to the other. In Khuzdul we have an indication about the phonemic set through the Cirth Tolkien provided in the appendices of LotR. These runes basically stand for a sound, or a phoneme. We have to assume that Khuzdul would write exactly what it hears, meaning that it is a phonetic script where silent symbols have no place. English used to have a phonetic spelling too, but as we all know, pronunciation and spelling have little in common today. In fact the English spelling provides a good view into the past of the language… as a German speaker I can read English as if it were German… and I get a good idea about the way it sounded five hundred years ago. Khuzdul still would have phonetic spelling.. meaning all symbols have a sound value… no unnecessary runes which are not pronounced. However, in the alphabet we are using it is not possible to reproduce these sounds adequately and Tolkien often opted for a combination of letters to describe one sound. This is important to know because Khuzdul as a rule does not allow double consonants at the beginning, and consonant clusters of more than two at all… That is a fixed rule… and to be able to read Khuzdul in latin letters we need to know what letter combinations describe what sound. In the runes every sound is described as only one rune, which means that reading the Angerthas Moria is less ambiguous than reading the latin transcript. Below I have drawn up the Cirth as they apply to the Khuzdul, disregarding the Elvish variations. Next to them are the symbols which would be used in the IPA (international phonetic alphabet [international that is except for the USA]) The red variants describe the Erebor variants which show a slightly different use of the runes. I have opted for the Angerthas set which means that there are no words containing an ‘x’

The runes are mostly arranged in pairs of unvoiced, voiced. If they are reversed they are fricatives, meaning, they produce a hissing sound as air is let to pass. Some notes on the phonetic symbols: The little raised ‘h’ means that the consonant is followed by a puff of air, giving it a greater strength. Tolkien himself only mentions th, kh, leaving it to us to conclude whether dh and gh would be aspirated voiced stops or fricatives. One could argue with parallelism…. But phonetic systems are not always parallel or logical. However, the character of the language leads me to believe that the voiced pairs should also be aspirated stops and not fricatives. The little ‘w’ after the consonant means that there is a lip rounding following the consonant which changes its quality. The vowels have given me some headache because Tolkien states that no language except Sindarin knows umlauts which in German are written as ä,û. This means that these two letters cannot actually denote an umlaut… they must have another value. As the text in the appendices uses for a long vowel the macron, that is the long slash over the letter the two points might indicate an overlong vowel. In the phonetic symbols this means u: denotes a long vowel, ŭ denotes an over length. At what point these overlong vowels can appear, however, is unclear. The question mark with the ‘ should actually be overturned and denotes a glottal stop… the sound the cockney make when pronouncing butter…. bu’er. It is considered a full consonant which, however, is usually placed initially. The upside down ‘e’ is called schwa and is an empty vowel… the vowel one produces when tongue and lips are in absolute repose. It is usually put between two consonants which would otherwise be fairly difficult to pronounce as for example the combination khw-g. As a proper vowel in between could changed the meaning of the word the schwa is used to make pronunciation possible. For writing purposes we use an ° here… for empty. Some other pronunciations: ch is pronounced as in chain, j is pronounced as in jean, gh is pronounced as in the middle English knight… a soft hissing sound, slightly voiced, not as rough as the Scottish loch (this would be its partner sound but Tolkien expressly notes that this sound does not exist in Khuzdul) s and z are the unvoiced and voiced pair of the same articulation while sh is pronounced as in she, zh is a voiced sh, pronounced as in the French garage. Y is the sound one finds in young, while ŋ is the final ng of young. Ng however is as in singer… a very faint g is audible there. For the vowels Tolkien gives the examples of machine, were, father, for, brute. All vowels are absolutely not diphthongised. Khuzdul would possess no diphthongs proper but diphthongisation can happen with w and y after a and i respectively, so khawlad would become khaulad. It is, however, important to realize that the u still retains its consonantal quality of radical root…. In another environment the u will become w again. | |

| Просмотров: 4240 | |

| Всего комментариев: 0 | |